Why the Middle East Matters

10,000 BC marks the start of the Neolithic Revolution, when humans became less nomadic and first began to practice agriculture. By 8,000 BC, diets had shifted dramatically, small towns had become cities and great empires arose in North Africa, Asia and the Middle East. During this age of discovery, human history started to evolve at a breakneck pace.

Our ancient ancestors were aware of the techniques of fermentation and storage. The first evidence of fermented alcohol was found in China, from the tiny village of Jiahu in Henan Province. Archaeologists discovered residue of a fermented mixture of rice, honey and grape in sealed pottery containers in the grave of a local shaman. It was determined to be from 7,000 BC. The grapes were Vitis Thunbergii, not from the same family as the grapes (Vitis Vinifera) generally planted worldwide for wine production.

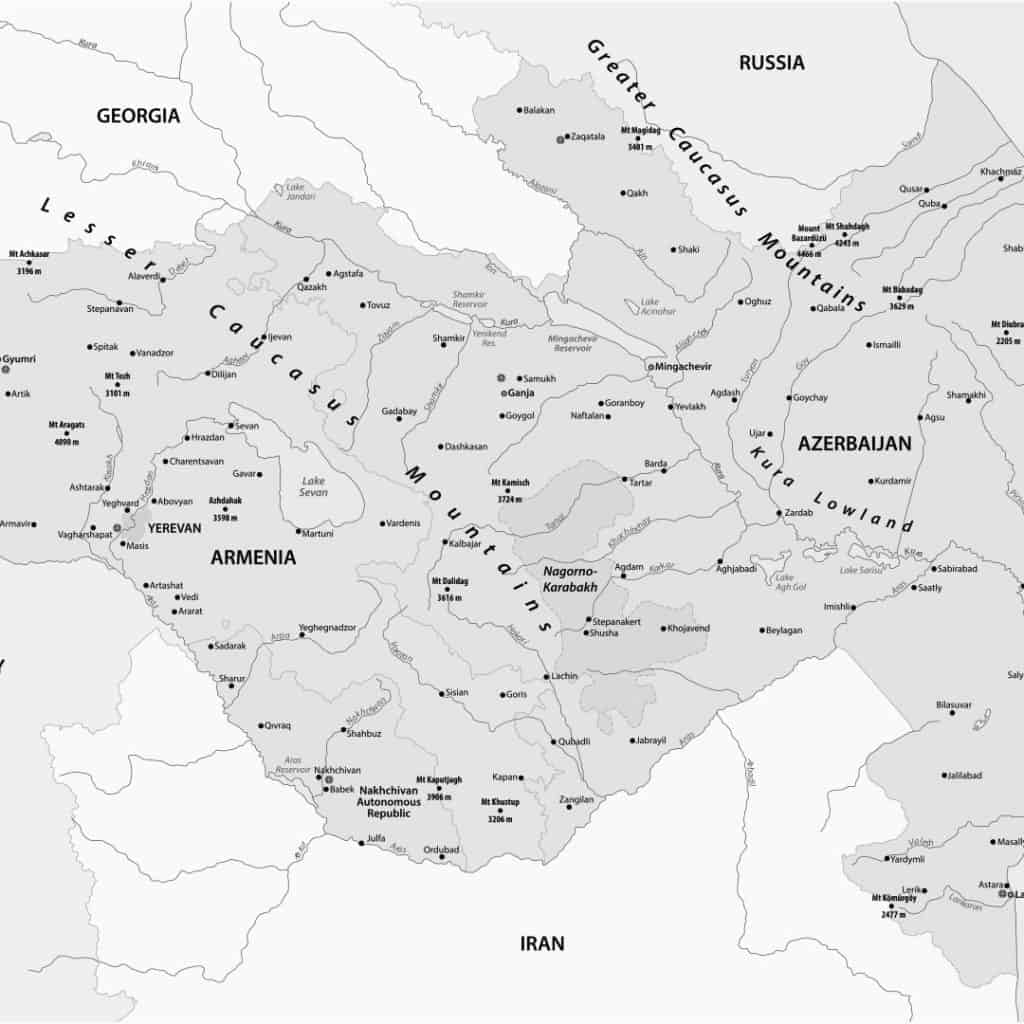

The birthplace of the Vitis Vinifera species of grape is the area of the Caucasus that includes Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, along with the Levant in the Middle East. The oldest remains of Vitis Vinifera production, dated to 6,000 BC, were found in Georgia, near Tblisi, in a place called Gadachrilli Gora. There, it was discovered that local farmers had been burying the juice of wild grape vines in pottery vessels and fermenting it, over the winter, to produce alcohol. The clay vessels found inside had decorations of grapevines on them, impressive considering the tools being used at the time were mostly stone and bone. Wine is still made in this way, in this region and throughout Georgia.

There is evidence of wine production in Iran in 5400 BC and the first known winery, dating to 4100 BC, was discovered in Vayots Dzor, Armenia, where chards of cups and pitchers, fermenting vats and Vitis Vinfera stems and seeds were found. Vitis Vinifera traces that date to 4000 BC have also been found in Greece. These grapes were not native to that region, so it stands to reason there were likely active wineries long before then.

Spurred on by the travels and dealings of the Phoenicians, the domestication of grapevines began in earnest throughout the Middle East, including Egypt, Sumeria, Carthage, Turkey, Greece and Greek Macedonia. By 3000 BC, wine production was fairly well-known and widespread.

The next seismic shift for wine came with the emergence of Imperial Rome. By 800 BC, there were reportedly grape plantings, brought by the Greeks, on Italian hillsides. It is said that the Legions marched on posca, a mixture of sour wine that had elevated levels of acetic acid, mixed with herbs, that was then mixed with water. The antibacterial elements of the acetic acid helped ensure that the water they consumed was potable, and the water helped cut the strong vinegar flavours of the sour wine. They also carried amphorae of wine for trade. During Rome’s glory, it occupied most of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Eminently practical, vinifera cuttings and vines, along with viticultural and vinification knowledge, were brought to the new outposts.

The most recent history of Middle Eastern wine is tied to the presence of colonial France in North Africa, as well as post-WW2 Lebanon and Syria. The Middle East had been largely under Muslim rule since the 7th century, so winemaking in many regions was on a small scale. Under the eyes of French settlers and officials, plantings were made of French vinifera vines in regions deemed suitable for viticulture. Countries like Algeria and Tunisia, that had been making wine since the days of Carthage, were revitalized in the 1830s and, by 1950, two-thirds of all wine exported in the world came from Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. The vast majority of it was hearty Carignan to be blended in the South of France with the local, light-bodied Aramon varietal. After Algerian Independence in 1962, and the departure of French settlers, Algerians struggled to find new markets for their wines. While the Soviet Union and a few other countries offered to buy bulk wines at deflated prices, the Islamic governments suggested that vineyards be turned to the production of table grapes and other crops. Algerian production declined dramatically as a result.

In the 1850s, Jesuit priests brought cuttings, mostly of Bordeaux varietals, from Algeria to Lebanon and planted them at Chateau Ksara in the Bekaa Valley. In the 1930s, a young man named Gaston Hochar returned to the Bekaa Valley, after travelling to Bordeaux France, and founded Chateau Musar. These wines drew the attention of the French Army stationed there in WW2. Hochar became friends with Ronald Barton, of the family linked to Château Leoville-Barton and Château Langoa-Barton, and Bordeaux took notice. The notoriety of Chateau Musar helped spur interest and investment in Lebanese wines, which today have become known for their high quality.

In the 1880s, Baron Phillipe de Rothschild of Chateau Lafitte-Rothschild began importing French varietals into what is today Israel and established Carmel Winery, near Haifa, in 1882. The country has expanded its winemaking capabilities since then, and now produces over 50 million bottles a year.